Oct. 8, 10:30 a.m., 2023: The day after Gaza on the U.S. -Mexico border

American Friends Service Committee aid station on the U.S. -Mexico border, the secondary fence at Whiskey 8, south of San Diego

The Day After Gaza on the U.S. Mexico Border

Whiskey 8, an open air detention area across the border from Tijuana, is mostly quiet now. But two years ago it was often crowded with migrants who were seeking asylum. Recently, it’s been rare for migrants to voluntarily surrender themselves to Border Patrol between the primary and secondary border fences that separate the US from Mexico. But two years ago, it was likely—if you were a migrant wanting to make an asylum claim--you could allow yourself to be arrested by Border Patrol at Whiskey 8 or at many similar places along the southern border. After being processed, and given a notice to appear, you would then be released into the U.S. In allowing millions to be given safe haven in this manner, Joe Biden paved the way for Donald Trump to retake the White House.

Until recently, there was a humanitarian aid station at Whiskey 8, on the U.S. side. It was managed by the American Friends Service Committee. Where volunteers handed out water, foodstuffs, clothes, medicines and supplies to the migrants on the other side of the fence, between the fence bollards. There was a cellphone recharge station. The migrants from all over the world: West Africa, South America, Pakistan. They had likely paid thousands to the cartels for their passage. Many had also likely experienced great trauma on their journeys. Robbery. Rape. Beatings. After June 2024, when Joe Biden tightened the rules for claiming asylum, the stream of migrants dried up (and so did the need for the humanitarian aid station). But it was too late for Biden, and perhaps too late for us. By us, I mean, anyone who cares about the Constitution and wants to live in a functioning democracy.

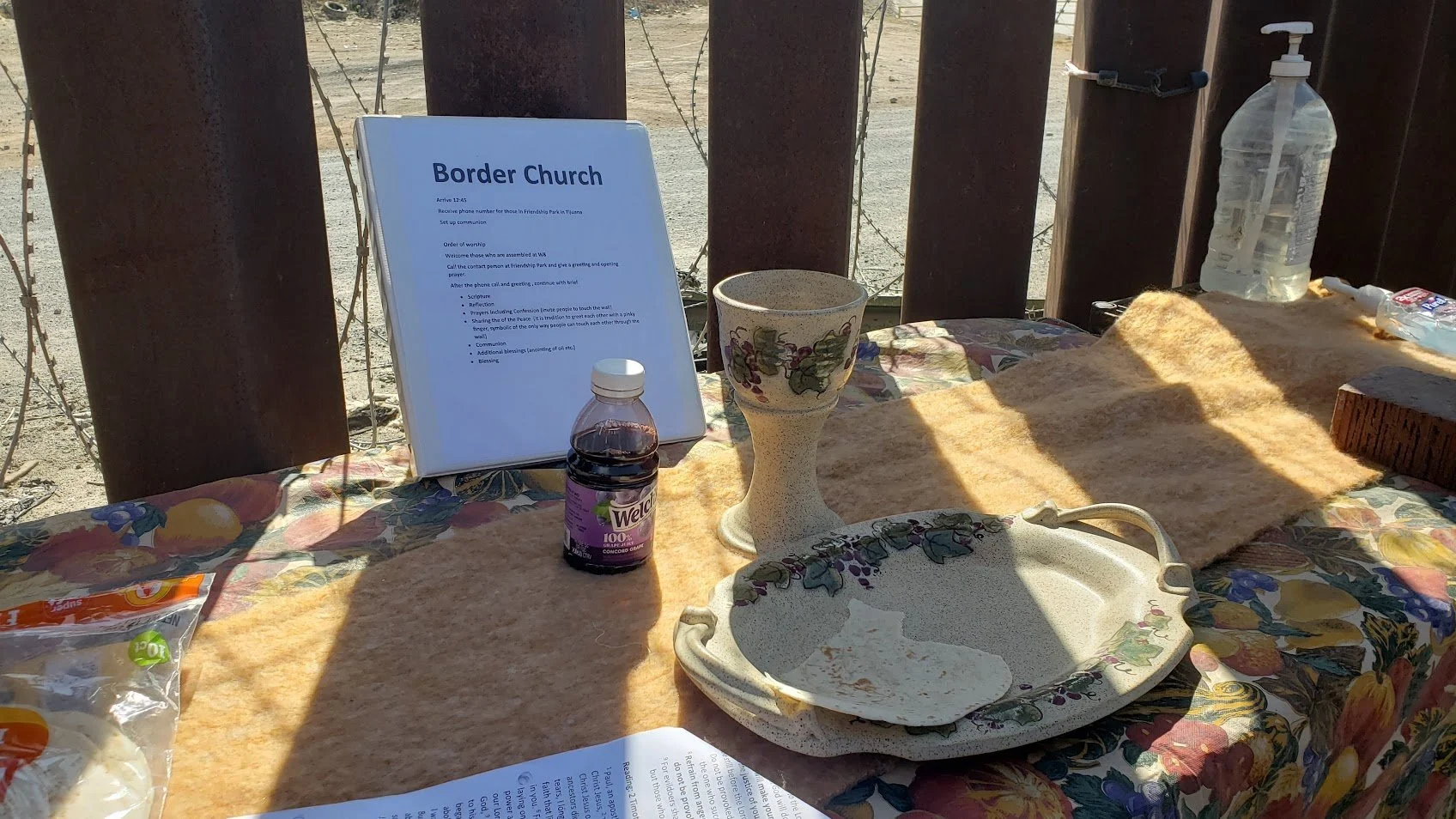

On Sundays, when Border Field State Park is not open, a pastor from one of the area congregations leads a service at the former AFSC aid station, right up against the secondary fence. It’s part of the weekly Border Church. Before June 2024, the pastors would minister to both San Diego congregants on the other side of the fence and the migrants, but now there are no more migrants. As the congregants pray, they are watched over by Border Patrol in close proximity. The pastors typically lead with a prayer, praying the border wall will crumble into the dust, before offering up the Eucharist. What follows is my journal of one very busy day at the Border, two short years ago, a day after Hamas crossed into Israel and killed 2,400, ensuring the destruction of Gaza.

Oct. 8, 10:30 a.m. 2023

I turn off onto the unpaved Monument Road towards Whiskey 8. Just where the road twists towards the border wall, an ambulance blows past me in the opposite direction leaving a cloud of dust in its wake.

I park in the gravel and walk to the tent-table stations set in on the dry ground along the secondary border fence, with its 30-ft.-high bollards. This time, opposed to the first time I visited a week ago, things are much more frenetic. As I park, I see dozens of migrants visible behind the secondary fence. They are at this point for a reason as it acts as an open air detention site for Border Patrol. It’s also where American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) volunteers have a station. This is where they prepare meals, handing food and medicine through the fence bollards with the cooperation and tacit approval of Border Patrol, which not only allows AFSC to distribute aid but directs migrants to their stations. Under the Biden administration, this kind of cooperation occurs all along the border, as Border Patrol does not have adequate resources to feed or shelter migrants or to even keep them all alive. So they rely on humanitarian nonprofits to close the gap the best they can.

I spot Adriana Jasso, the program coordinator for the AFSC US Mexico Border Program, whose smile signifies a relentless practical optimism.

I ask her what’s different compared to my last visit.

“We have actual doctors that are here attending,” she says. “We had two medical emergencies about 30 minutes ago.” She nods to the near distance, where there is a woman wearing a traditional African skirt over yoga pants seated on a folding chair, her bare foot up on a crate, surrounded by paramedics. “She fell from the wall at 4 a.m. She can't walk.”

“I saw an ambulance,” I say.

“That one was a lady who is three months pregnant,” Jasso recounts. “39-years-old, from Romania. She has three kids and had heavy bleeding through the morning,” Jasso says. “I would say one really good person to talk about the whole thing since we have one right now is Dr. Alex Tenorio in the blue.”

Tenorio, however, looks preoccupied at the moment. The wiry, athletic looking doctor is conferring with some of his colleagues.

As it happens, I recognize Tenorio’s name, having recently read an op-ed in the L.A. Times by the young San Diego based neurosurgeon. In that piece, after outlining his own history as the son of Mexican immigrants who had fled violence in their hometown, Tenorio writes about the increasing number of injuries he’s encountering in the hospital where he works.

“When I care for people fleeing similar violence, I know that they are searching for the same things that my parents did and that we all do: safety and a chance for a better life for their children,” he wrote. “As a neurosurgeon, I am horrified by the rash of traumatic brain and spinal cord injuries caused by falls from the border wall.”

Tenorio suggests a correlation between the more severe injuries that he’s seeing and higher border fencing, a correlation that he has also written about extensively in professional journals.

I walk up to the fence to talk to the migrants. Having crossed over or under the primary fence bordering Tijuana, they were now stuck, at least for the time being, in the detention site with little to offer but tarps for shade, some decrepit looking porta-potties, trash, and dust. They were just two miles away from the Las Americas Premium Outlets, and its version of the American Dream—window shopping Armani with Starbucks in hand. A little bit farther east, the San Ysidro Port of Entry, the busiest land border crossing in the Western hemisphere, was within view.

I approach a young woman in a traditional African blouse, skirt, and scarf. She’s clasping the fence bollards, looking through the space between, looking for someone to talk to and greeted her in French—guessing that she’s from West Africa where the language is widely spoken. She responds, telling me her name: Mariama. I try to engage her in conversation but she’s really not into it, explaining to me that her leg is injured and she has a stomach ache. The best I can get from her is her country of origin: Guinea, and she was traveling in the same group along with the woman being treated by paramedics—on the other side of the fence from her.. Like the dozens of others I see walking around or taking shelter in this open-air detention facility, she is waiting for Border Patrol to process her, and give her a notice to appear at some future date to make her asylum claim.

I relay the leg injuries to one of the doctors running around. He’s chubby, looks like he started growing facial hair yesterday. He tells me curtly, “We know,” and he goes on to tell me even more curtly that he doesn’t want to share his information with journalists or have his conversation recorded.

But Dr. Tenorio overhears me and decides to respond. He walks over to the fence, kneels down and inspects the woman’s foot as best as he could; examining it by sticking his hands through the four-inch gap between the fence bollards. One of his colleagues, a woman in her 40s, is translating into French for the doc, who concludes his examination with a diagnosis of a broken metatarsal. Tenorio asks Mariama if she wants some Tylenol. This is about the best he can do, considering the barrier between them. He then explains the injury to Pedro Rios, the director of AFSC’s border program.

Rios, wearing a ballcap and a relentlessly calm expression, explains some complicating factors to the doctor, so he can explain it to her and she can make the decision whether to ask to go to a San Diego hospital or to grin and bear it. It’s a tough decision. If she goes to the hospital, Border Patrol would not provide her with any document that would allow her to remain in the US.

“So, what happens if she goes to the hospital, and Border Patrol won’t provide her with any document?” Rios asks Tenorio, more in the way of creating a scenario rather than asking a rhetorical question. “Then she would have to turn herself into ICE involving expedited removal or she would have to apply for asylum on her own. If she goes to hospital her situation becomes much more difficult.”

Tenorio goes back to the fence, I assume, to explain this situation to Mariama. Then Rios looks sharply over my shoulder, towards the meal preparation tent, where someone is calling to him in Spanish. “Excuse me,” he says, and walks in that direction. Walking past me is the intense-looking woman who acted as a French translator at the fence, who is now speaking Spanish with one of the volunteers with a disgusted look on her face. I catch some of her anger towards the ad-hoc nature of the response to this ongoing humanitarian crisis. Standing nearby is a Border Patrol agent, probably in his late 30s, who looks just a little frazzled by what’s going on. I tell him I’m a journalist, but I reassure him that I’m not going to use his name if he answers my questions.

Nodding to the African woman with her foot up on the crate, who is still being tended by paramedics, I ask him how many have fallen from the fence today.

“Twenty people fell not just here but the whole area from 6 a.m. to now,” he says, meaning the whole area, the entire stretch of San Diego county border. He excuses himself to take a call on his cell phone.

So I approach the intense-looking woman who acted as a French translator, who had impressed me by switching at a moment’s notice to Spanish, and we start talking. It turns out that, like Tenorio, she’s another physician who works at a San Diego-area hospital. I ask for her assessment of the situation at Whiskey 8 and she agrees, providing I keep her name out of it.

“The federal government should be here and have a presence beyond Customs and Border Protection,” she says. “FEMA should be here. National Guard physicians should be here. The feds need to allocate significant funds and give the Centers for Disease Control division of quarantine and migration authority to do medical care coordinated across the country border shelters across the country and do appropriate medical screening and and then funding needs to be allocated to link asylum seekers to housing, safe places to live and to immigration lawyers. Okay? Period.”

With that, she walks off.

A little while later, as the paramedics start loading the woman—who’s from Guinea, I find out, after asking her—into the ambulance, the translator starts conferring with Dr. Tenorio and some other volunteers gathered there.

The Border Patrol agent soon invites himself into this conversation, spurring some incredulous glances. I just so happen to be listening in.

“So last week, I went to pick up my wife at the airport,” he says. “There were people there that were here two days before that. And they recognized me and they were like, Oh, you're a good cop. You're a good cop. So that warms my heart. You know, I'm human. They're human and I want to do the right thing. Even though I have a uniform on, my heart is in the same place. My hands are tied. We're not getting help from anywhere. It's just a mess right now. We're trying. I appreciate what you guys are doing. A human life is a human life.”

It was good to hear him say this, I suppose, especially in light of the tacit cooperation I’ve seen between AFSC and Border Patrol at the border. It’s better than the zero tolerance approach of the prior administration. But his pieties won’t make any difference if Donald Trump wins a second term as president. In that eventuality, his apparent sympathies towards migrants could put his job at risk.

Border Church at Whiskey 8